Wales at War: The sources of UXO contamination along the southern Welsh coast

The risk of encountering unexploded ordnance (UXO) in the UK as a result of World War II is not limited to London. Through a series of posts, Artios looks at the potential of UXO contamination at different locations across the UK.

Luftwaffe Aerial Reconnaissance photo of the Swansea Docks.

German bombers over Britain

The Battle of Britain, fought mainly through July – October 1940, has the unique distinction of being, perhaps, the only battle in the history of warfare to be fought entirely in the air and at sea. While the battle ultimately ended in the failure of the Luftwaffe to defeat the RAF and gain control of the skies over Europe; for many months that followed, much of the country faced the full fury of German air power as it attempted to bomb the nation into submission.

Until the summer of 1940, Wales, along with most of the UK, was well out of range of German bombers operating out of airfields within Nazi-controlled territory. However, with the fall of France in June of that year, the Luftwaffe was flying out of Cherbourg, Calais and other airfields in northern France - only minutes away from the English coast.

The systematic and sustained bombing campaign of Britain launched by the Germans in September 1940 was initially centred over the capital and is well-known today as the ‘London blitz’. But soon after, several other cities and towns in Britain found themselves under the bombsights, as World War II arrived at their doorsteps.

The Wales Blitz

The 12th century Llandaff cathedral severely damaged after an enemy bombing raid.

South Wales is home to a number of important docks and harbours such as Swansea, Newport, Port Talbot and Cardiff. These were not only important centres for industry, commerce and trade but were also crucial during wartime for much needed supplies to reach Britain from across the Atlantic.

While the last few months of 1940 brought several bombing raids over Welsh towns and cities, the most devastating attacks came in early 1941. There are, even today, survivors who grimly recall Cardiff’s night of terror on January 2nd, 1941. The full-moon or ‘Bomber’s moon’ that night, set the stage for the worst bombing hit yet suffered in Wales. The wail of the air raid sirens was soon followed by the foreboding throb of the Dornier and Junkers engines over the city as they crossed the Severn estuary. The first bombs struck at 6.37 pm and continued to fall for over ten hours. Over 150 people were killed and dozens of buildings destroyed. Some of the worst damage was suffered in Grangetown, Canton, Roath and Riverside, where 50 people were killed at De Burgh Street alone. Even the iconic LLandaff cathedral was not spared, as the thousand-year-old building suffered extensive damage from a parachute mine detonating in the churchyard. phase 1

The worst, however, was yet to come. Infamously known as the ‘3 Nights Blitz’, Swansea was bombed for three consecutive nights between 19-21 February 1941 with over 30,000 high explosive and incendiary bombs being dropped over the city. The results were catastrophic – over 800 buildings and 40 acres, including much of the city centre, were left in complete ruins and over 200 people were killed, with scores more injured or made homeless. Mayhill, Brynhyfryd, College Street, Cwmbwrla, Townhill, Manselton and many other parts of the city were all reduced to rubble.

Swansea city centre lies in ruins after the ‘3 Nights Blitz’ in February1941.

A tragic irony that played out here in Swansea and repeated itself in many other places, was that although the docks were obvious, strategic targets; they suffered relatively minor damage compared to densely built residential areas located immediately inland to them. This is likely due to the small target profile they presented to enemy bombardiers flying in over the water at over 4000 ft; and a delay of a mere second or two in bomb release meant that weapons aimed at the docks landed amidst homes and businesses.

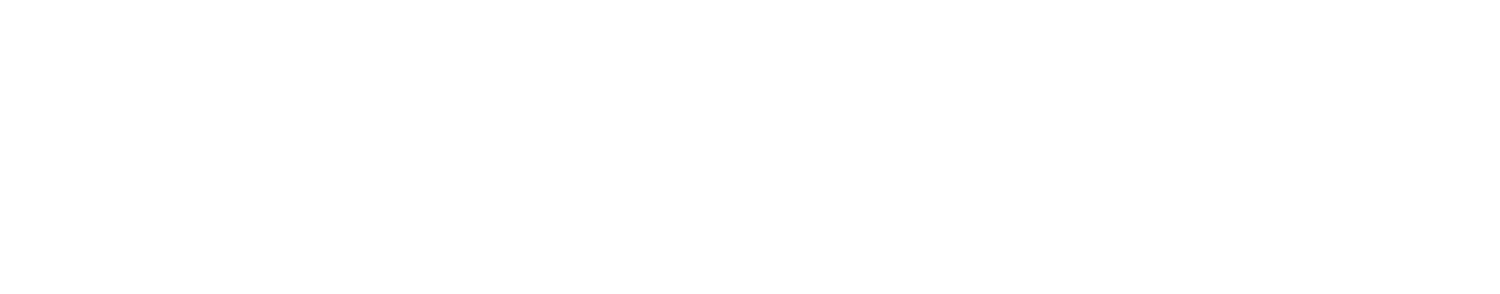

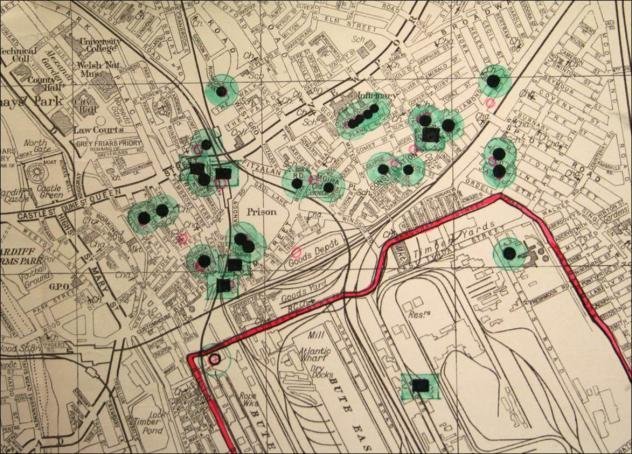

Luftwaffe target map of the Penarth Docks.

Ominously, the Luftwaffe’s list of targets was not restricted to the big cities alone and the fires of war soon spread to the hinterland as well as other ports. Apart from several defensive positions against potential enemy invasion, South Wales also housed several operational RAF airfields with their compliment of decoy sites, support installations and protective anti-aircraft batteries - all too well noticed by the enemy. During the war years, a number of other locations in southern or south-western Wales were hit by repeated bombing raids, most notably :

· Bridgend

· Llandow

· Newport

National Fire Service sketch depicting bomb hits immediately north of the Cardiff docks.

· St Athan

· Port Talbot

· Ogmore

· Pembroke

· Penarth

· Barry

· Boverton

D-Day training in Wales

The invasion of Normandy by the Allies in June,1944 marked a turning point in the war. Already, the German army was on the defensive in Italy with Allied armies sweeping across the country. But to ensure success on this new campaign, months of preparation were required in terms of training as well as the build-up of logistics.

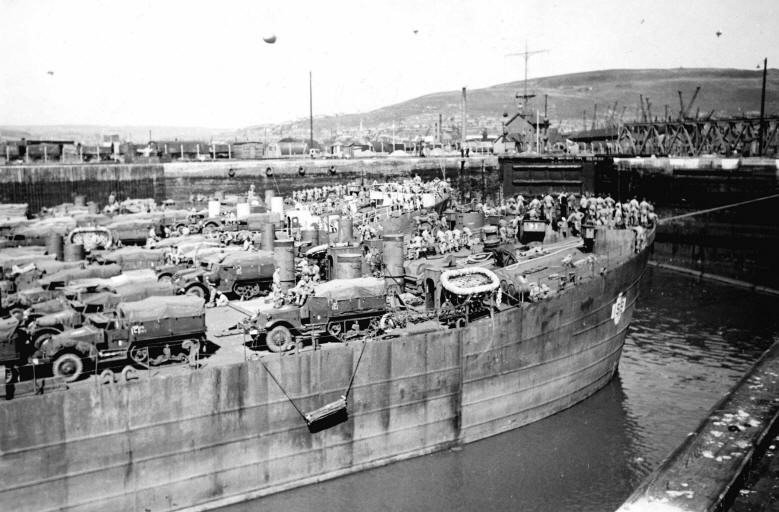

Allied troops aboard Tank Landing Ships(LST) at King’s Dock, Swansea prior to the D-Day invasion in 1944.

The ports and harbours of South Wales provided the ideal staging areas for an invading force and by the spring of 1944, Cardiff, Gwent, Newport, Monmouthshire ,Port Talbot, Pembry, Barry and Swansea were teeming with not only British but also hundreds of thousands of US & Canadian military personnel. Storage depots for ammunition, equipment and supplies, marshalling areas for lorries, tanks and other vehicles along with barracks and accommodation for troops; were all set up in and around various coastal cities and towns.

Rehearsals for the planned Normandy landings are carried out in Pembrokeshire in 1943.

Tactical training including practice fire of various weapons was regularly conducted at the Kenfig sand-dunes and the Gower peninsula, among other places such as Gaer Fort, Newport which had been used throughout the war for training of the Home Guard. Interestingly, the layout of beaches and terrain along the southern Welsh coast was thought to be very similar to that of Northern France, where the invasion was planned to take place. Training manoeuvres began in Pembrokeshire almost a year before and Tenby, Saunderfoot and other areas were placed under strict curfew in the summer of 1943 as rehearsals and simulated beach ‘invasions’ were conducted by Allied troops.

Explosive Remnants of War or UXO are still found today, at such former military training areas.

Implications for the Construction Industry

The bombing of major cities by enemy aircraft, in South Wales as well as the rest of the UK, was well publicised during and after the war and is, naturally, the first association made with potential UXO risk. However, what is sometimes overlooked is that there is a far greater chance of UXO contamination from other sources such as military land use all over the UK for training or storage of ordnance, both during WWII and in the decades that follow.

It is estimated that over 20 percent of the UK was used by the military for a multitude of purposes during WWII, often for practice firing or testing of high-calibre weapons. Due to the uncertainty, hastiness and chaos that comes with war, it can be assumed that the notification and clearance procedures at these firing ranges may have been ad-hoc and superficial, at times. The same also holds true for the disposal of large quantities of unused ordnance by foreign armies leaving the UK and storage depots closing down after the war.

While large, unexploded aerial bombs pose an enormous risk to life and material when disturbed, their discovery is relatively infrequent. Depending on the location within the country, there may be a greater likelihood of encountering smaller but more proliferous UXO; thus elevating the risk of business interruption even if that of physical danger is lower. Some examples of such contamination are:

Unexploded WWII high explosive mortar found at Kenfig Pool, Bridgend in 2014.

· Unexploded anti-aircraft munitions fired by defensive batteries.

· Unexploded or hastily discarded hand-grenades, shoulder-fired rockets, mortars and other infantry weapons fired at practice ranges.

· Uncleared or abandoned land/sea mines laid for defensive purposes.

· Unexploded artillery munitions fired by enemy units (cross-channel) from occupied territory.

A construction professional about to break ground at a new site may or may not have considered the risk of UXO encounter prior to conducting intrusive works; based on general assumptions about an area drawn from evidence that may, at times, be misleading. For example, very heavily bombed areas of Cardiff may actually have negligible UXO risk today due to intensive post war development. Such assumptions may, therefore, lead to expensive mitigations being implemented unnecessarily.

Unbiased and bespoke UXO Risk Assessments

Only a thorough analysis based on comprehensive and systematic historical research of an area that factors in all relevant considerations allows for the risks to business, life and material to be assessed correctly. Artios Global provides unbiased and bespoke UXO Risk Assessments designed in accordance with industry standard publications CIRIA C681 and CIRIA C785, which have been developed specifically to help construction professionals understand the risks from UXO and employ suitable mitigation measures. Artios provides no on-site survey or mitigation services and thus can assure its clients of complete impartiality in its risk assessments, with no vested interests in securing further business from any mitigations that may be recommended.